New works by TIMO HOGAN will be released on 03 Mar 2026

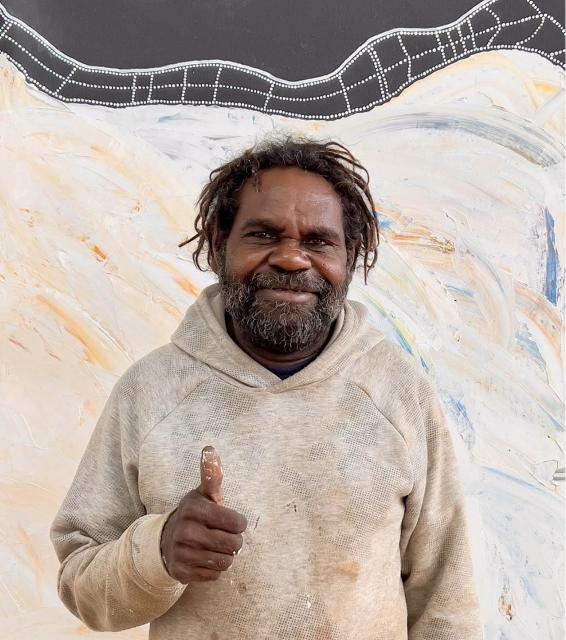

Timo Hogan, one of Australia's most compelling and celebrated voices in contemporary Indigenous art, represents the brilliance of a second generation of Spinifex painting talents.

His mother, the artist Anne Hogan, fled her nomadic homelands to escape British nuclear testing in the Great Victoria Desert, at one point burying herself in a sand dune with family members as protection from "the big smoke." She settled at the Cundeelee Mission where she met Neville Niypula McArthur, the spiritual caretaker of Tjukurpa (creation dreaming) associated with Pukunkura (Lake Baker).

He would later pursue his painting practice at multiple Indigenous art communities including the Warburton Art Project, Kayili Artists, Warakurna Artists, and the Spinifex Arts Project.

Anne bore their son, Timo, at a hospital in nearby Kalgoorlie.

Observing his mother's art practice as a young adult, Hogan experimented with painting without fully committing to it.

A transformative moment came in 2018 upon visiting his father's hospice bedside and making a sojourn immediately afterwards to McArthur's birthright country, the vast and remote salt pan of Lake Baker.

The pilgrimage to his father's birthright site proved galvanic: "It was like watching the unlocking of a series of doors with memory concealed behind each" recalled Brian Hallett, the Spinifex Arts Project studio manager at the time.

Embracing his role as the sites traditional caretaker, Hogan returned to the Spinifex community of Tjuntjuntjara invested with renewed authority to paint the spiritually powerful Tjukurpa of Lake Baker's Wati Kutjara (Two Men).

In his monumental paintings, Hogan reenacts the primordial story of ancestral beings that gave shape to the landforms of Lake Baker.

Due to the millmillpa (dangerously potent) metaphysical resonances of the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa narrative, its storyline can be related only in rough outline.

Two ancestral men, depicted by Hogan as abstract roundels, cautiously watch the lake's resident Wanampi (water snake being) slithering from its rock cave and skirting the dry shoreline: a fearsome creature aware of being observed.

Capable of both benevolence and ferocity, the water serpent is as white as the lake's dry salt crust, reinforcing its supernatural powers.

Another episode of the narrative sees the two men spearing the Wanampi, causing it to writhe and carve the lake's boundaries.

As the three ancestral beings move through the environment, they carve indelible traces of their presence: the sites defining landmarks.

Hogan's artworks map Lake Baker as physical landscape and spiritual songline.

With a palette knife, he layers tones and textures to evoke the dry lake's shimmering surface in creamy whites, earthy ochres, and a splattering of muted colors.

Trails of white dots trace the tracks of the two men, delineate geographic boundaries, and outline the Wanampi's serpentine form and segmented body, suggesting its internal forces.

Hogan's minimalist compositions convey the ominous power of the Wanampi in indirect glances, honouring the secretive protocols of the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa while transmitting a sense of its spiritual depth to his global audience.

Profound meditation on the power of place, Hogan's work blends painterly abstraction with cultural storytelling to create pieces that feel both intimate and epic.

Critics and collectors praise his creation of a refined visual language that captures the sacredness of Spinifex Country through a subtle interplay of tones and textures that evoke an indelible ancestral presence.

Transcending literal representation, his paintings embody Lake Baker's sentient energy and cultural law, echoing modernist abstraction while remaining firmly rooted in Indigenous ontology.

A landmark achievement came in 2021 when Hogan won the prestigious Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA), Australia's longest-running Indigenous art prize, cementing his status as a leading talent in Indigenous art.

The award, , Australia's longest-running Indigenous art prize, recognized his ability to weave personal and communal histories into striking visual narratives.

Judges described the winning canvas as a "masterful painting of international calibre" from a "remarkably confident artist with talent that exceeds his age and experience." This marked the first time an artist from the Spinifex Lands won the overall prize, and Hogan (then in his late 40s) was one of the youngest finalists that year.

Hogan himself described the win as opening his heart, reflecting the emotional and cultural depth he invests in each piece.

Hogan has been a finalist in the Wynne Prize (Art Gallery of NSW, 2024) for another Lake Baker work, highlighting his ongoing critical recognition; his works also have been featured in high-profile exhibitions like the National Gallery of Victoria Trienniale (2023–2024) and Adelaide's Tarnanthi Festival.

.New works by TIMO HOGAN will be released on 03 Mar 2026

Timo Hogan, one of Australia's most compelling and celebrated voices in contemporary Indigenous art, represents the brilliance of a second generation of Spinifex painting talents.

His mother, the artist Anne Hogan, fled her nomadic homelands to escape British nuclear testing in the Great Victoria Desert, at one point burying herself in a sand dune with family members as protection from "the big smoke." She settled at the Cundeelee Mission where she met Neville Niypula McArthur, the spiritual caretaker of Tjukurpa (creation dreaming) associated with Pukunkura (Lake Baker).

He would later pursue his painting practice at multiple Indigenous art communities including the Warburton Art Project, Kayili Artists, Warakurna Artists, and the Spinifex Arts Project.

Anne bore their son, Timo, at a hospital in nearby Kalgoorlie.

Observing his mother's art practice as a young adult, Hogan experimented with painting without fully committing to it.

A transformative moment came in 2018 upon visiting his father's hospice bedside and making a sojourn immediately afterwards to McArthur's birthright country, the vast and remote salt pan of Lake Baker.

The pilgrimage to his father's birthright site proved galvanic: "It was like watching the unlocking of a series of doors with memory concealed behind each" recalled Brian Hallett, the Spinifex Arts Project studio manager at the time.

Embracing his role as the sites traditional caretaker, Hogan returned to the Spinifex community of Tjuntjuntjara invested with renewed authority to paint the spiritually powerful Tjukurpa of Lake Baker's Wati Kutjara (Two Men).

In his monumental paintings, Hogan reenacts the primordial story of ancestral beings that gave shape to the landforms of Lake Baker.

Due to the millmillpa (dangerously potent) metaphysical resonances of the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa narrative, its storyline can be related only in rough outline.

Two ancestral men, depicted by Hogan as abstract roundels, cautiously watch the lake's resident Wanampi (water snake being) slithering from its rock cave and skirting the dry shoreline: a fearsome creature aware of being observed.

Capable of both benevolence and ferocity, the water serpent is as white as the lake's dry salt crust, reinforcing its supernatural powers.

Another episode of the narrative sees the two men spearing the Wanampi, causing it to writhe and carve the lake's boundaries.

As the three ancestral beings move through the environment, they carve indelible traces of their presence: the sites defining landmarks.

Hogan's artworks map Lake Baker as physical landscape and spiritual songline.

With a palette knife, he layers tones and textures to evoke the dry lake's shimmering surface in creamy whites, earthy ochres, and a splattering of muted colors.

Trails of white dots trace the tracks of the two men, delineate geographic boundaries, and outline the Wanampi's serpentine form and segmented body, suggesting its internal forces.

Hogan's minimalist compositions convey the ominous power of the Wanampi in indirect glances, honouring the secretive protocols of the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa while transmitting a sense of its spiritual depth to his global audience.

Profound meditation on the power of place, Hogan's work blends painterly abstraction with cultural storytelling to create pieces that feel both intimate and epic.

Critics and collectors praise his creation of a refined visual language that captures the sacredness of Spinifex Country through a subtle interplay of tones and textures that evoke an indelible ancestral presence.

Transcending literal representation, his paintings embody Lake Baker's sentient energy and cultural law, echoing modernist abstraction while remaining firmly rooted in Indigenous ontology.

A landmark achievement came in 2021 when Hogan won the prestigious Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA), Australia's longest-running Indigenous art prize, cementing his status as a leading talent in Indigenous art.

The award, , Australia's longest-running Indigenous art prize, recognized his ability to weave personal and communal histories into striking visual narratives.

Judges described the winning canvas as a "masterful painting of international calibre" from a "remarkably confident artist with talent that exceeds his age and experience." This marked the first time an artist from the Spinifex Lands won the overall prize, and Hogan (then in his late 40s) was one of the youngest finalists that year.

Hogan himself described the win as opening his heart, reflecting the emotional and cultural depth he invests in each piece.

Hogan has been a finalist in the Wynne Prize (Art Gallery of NSW, 2024) for another Lake Baker work, highlighting his ongoing critical recognition; his works also have been featured in high-profile exhibitions like the National Gallery of Victoria Trienniale (2023–2024) and Adelaide's Tarnanthi Festival.

.